People of Moscow

There is a custom which still exists in some places in Moscow, which is the habit of sitting down when it is time to say goodbye. The nervous moment before leaving, tears or hysterical laughter, are all held in check for just a few moments. Everyone sits, simply waits, and holds his breath. It is like a short wake, a silence that lasts sometimes less than a minute. Like a prayer or a wish. The promise that you will meet again, knowing it is untrue or highly unlikely. Each one sits, avoids looking around him, and stares straight ahead. They could be looking inside themselves. It is a soothing moment, both magical and peaceful, shared serenity within the sadness that separation inevitably provokes.

The photographs in this book resemble this kind of moment. Most of the women in them are photographed seated, in their homes, sometimes outside, and those who are standing (or even more rarely, standing outside) are also pictures of calm. No-one is moving, the body is perfectly still, barely a heartbeat. Everyone is at a standstill. They are familiar with the person before them, his eye hidden behind the camera. They have met him before, at least once. It is easy to imagine the subjects remembering these meetings in the distant past, what has changed, what has remained the same in Moscow, this turbulent city. The photo is the high point of their reunion.

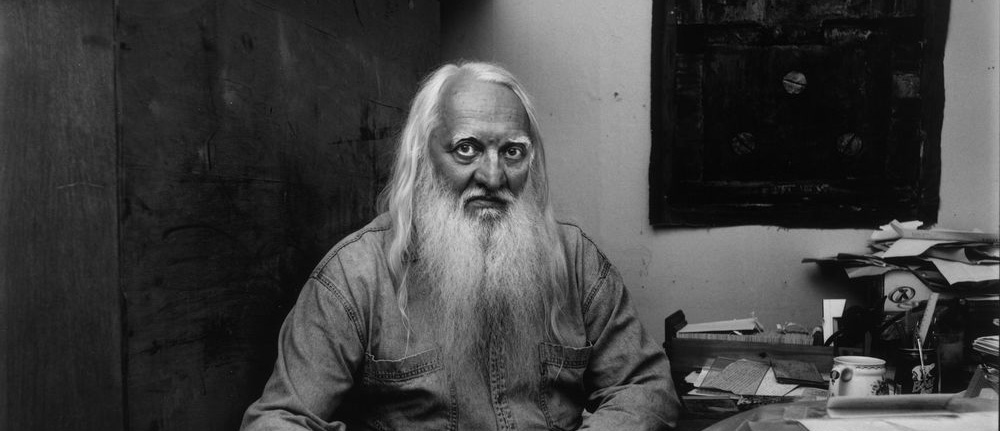

Here they all are, together again for the first six months of the year 2000, the time-span during which all the photos were taken. However, this particular moment is like no other. Having spent the past ten years in Moscow, the photographer Ahmet Sel is returning to Paris to live. Everyone knows about his departure, Ahmet told them, and said he would like to see them one last time before he leaves. He wanted to see his friends and thank them for simply being there, for having shared a part of Russian life with him, and to say goodbye. So they posed for him, serenely, and offered Ahmet Sel a photographic souvenir of themselves with all the memories of past years intermingled.

A stolen moment, a snatched photo taken in flight. There is complicity between the photographer and his subjects. A little solemn, as it should be, there is also an element of respect present. All portraits have a short life-span. The act is both serious, as both parties will separate maybe forever, and lighthearted. Each one will go his own way. Life goes on.

Many foreign photographers who stay in Russia just long enough to do a feature don’t see this life. They simply “observe.” They are reduced to being observers. What they “see,” the contact sheets they bring back, are often a series of images preconceived in their mind’s eye, prepackaged scenes that are visually verbose, such as street kids, alcoholics, prostitutes, the mafia. It all exists of course, and the disastrous results on society are overwhelming: orphans, the homeless, slaves, the murdered. Russia is certainly not a model of democracy. Subjugation and shamelessness is part of the daily diet, violence is everywhere. However to reduce Russia to this, is to reduce it to mere imagery, to a mess. Another common mistake is to perceive Russia through a prism that reduces it to the centre of Moscow, the capital that absorbs 80% of the country’s wealth, with its casinos, Mercedes, Cherokees, its trendy restaurants, clubs, mobile phones on Red Square, top models, the Goum shopping malls transformed into western malls with luxurious decor, its exorbitant hotels, the Pushkin Café inaugurated by Gilbert Bécaud, the biggest McDonalds in the world, its shop windows lit up that resemble nothing that recalls Soviet times. This flashy Moscow is totally different from the old one. Other photographers, often the same, are often blinded by this new Moscow and only show the glittering exterior of this outer skin without ever trying to get under the derma to reach the ordinary Moscovite.

Then there are other foreign photographers, those who visit and return, stay a little longer, are seduced by the city and end up living in Moscow and travelling all over the country. Ahmet Sel is one such photographer, one in a million. They photograph Russia from the inside. They are the only ones who have overcome mere appearances which are inevitably misleading, to reach the heart of the subject and the people, the actual substance of Russia. Even in the centre of Moscow today, the countryside, the past still exist. Many Muscovites were not born in Moscow. As is often the case in large capitals, the population have come from all over the country. Moscow is a sorting station, a crossroads where all paths converge. It is this Russia made of several different components that Ahmet Sel offers us, a magnificent subjective glimpse of the Russians he met who live in Moscow.

Do not bother to look for a sociological slant, or be surprised not to find Chechens or Caucasians in this photo gallery, or indeed any representation of the northern peoples. Ahmet Sel went to Chechnya, to the Caucasus he knows these places very well, and has produced several features there, but that is not the subject here. This is his personal panorama, the portrayal of a city and of those who live there “and have always done” apparently. As we look at some of the people photographed by Ahmet Sel, we often wonder when the photo was taken? Time seems to be vague, floating somewhere between today and yesterday, no fixed era, composed of ageless relics, trinkets, and jewellery from another world, portraits of ancestors, friends, children, wardrobes with winter and summer clothes mingled. Even the troublemaker Zinoviev is there. Look at his picture. In 2000, this destroyer of the Soviet regime had just returned from years of exile in the west.

One would think he would be effected by this other life. But no. The way he poses, with his hands behind his back, looks like an old class photo, his heavy jacket dating from Soviet times. This doesn’t mean that time has stood still in Russia. On the contrary, the bland building that pop up behind him were only built 20 or 30 years ago, despite their decrepit appearance. Time passes quicker in Moscow than it does anywhere else in Russia. However, one era doesn’t destroy another and sticks without fading, superposed with traps and improbable meetings.

Nothing seems to have changed in the deep heart of the Moscow underground, the most beautiful in the world as well as the safest. The same Soviet mosaics are in place, the same martial marbles, the same ticket sellers in the sentry boxes where everything is written by hand. On one side ads stretch the length of the never-ending escalators decorated with lamps of yesteryears. We meet youths in jeans and T-shirts with English words printed on them. In the evenings when there is a match the supporters, who include skinheads, wear Moscow Spartak scarves and there is little to distinguish them from any other football supporters in the world. Taking another escalator and stopping at the top, we come to a self-service photo booth, common in many stations. Unthinkable just 10 years ago. This revolution has been tinkered with to suit Russian needs. In the Moscow metro, these booths are tended to by old “babushkas.” She waits for her customers, she puts in the coins, advises how he should sit, waits with him to see the identity photos, congratulates him like a real grandmother who wants to share this special moment. It is a way of earning money, to improve a miserable retirement, but she takes pleasure in it, enjoys meetings with strangers, a brother, a son. Belonging to a nation is important in Russia among all those who lived the war against the Nazis. In a way, Ahmet Sel is like these guardians of the Muscovite photo booths.

Undoubtedly their dreams come true. One thing is sure, the babushkas are upset sitting at the back of the neutral white cabins, where the identity photos are taken. They would prefer if there were a more personal touch. They would be happy if the person took up the whole background, and filled the frame. If only the babushka could see the portraits in this book, she would be delighted. She would recognise her people, the Muscovites.

Ahmet Sel didn’t want to create a gallery of stars. There are of course some artists here famous worldwide, such as the director Anatoli Vasiliev or Youri Lioubimov, Soviet-Russian theatrical stars like the singer Iossof Kabzon, personalities from the New Moscow such as the dress designer Valentin Youdachkine or the avant-garde Muscovites, like Andrei Barteniev or Oleg Koulik. However, most are unknown: engineers, lion tamers, dancers or designer, practising Orthodox or striptease, transvestites or truck-drivers, contemporary music composers or opera singers, a young girl down on her luck or the ageing niece of Stanislavski, accordionist or baritone, deputy and poet, language student or former sergeant in the Russian army wounded in Grozny, housekeeper or chief editor of the paper “Old Believers” former fighter pilot or young businessman, school headmistress or car designer and figure painter? Surgeon or precursor of the Russian hippy movement, collector of modern art or undertaker…

An intimate cast, an album of acquaintances to whom the photographer is grateful. Although the portraits are personal, in their entirety they become a different, single portrait, that of the Moscow family, “the Muscovites.” A group photo with several angles of these individuals, strong and ever-present.

They all look like Muscovites, but each one brings a different aspect to the photo. Ahmet Sel has photographed the group from a perfect distance, not too close, not too far away. Each one, usually standing, has a frame in which to stretch, as if their “camera pose” carried on after the appointed time. The portrait enters a literary sphere. Proust would have loved these shops filled with accessories which reflect the typical Muscovite interior and appear in many of these photos. The literary sphere permeates everything, even the exterior, even a garden. The white-haired woman with her hands crossed on her over-sized pullover reminds us of Chekov’s Seagull. More precisely, of Nina. Is it because of the white bird, white like the pullover, or because of the garden she sits in which is like the one in which Treplev builds a makeshift theatre and throws Nina on the stage, making her utter magnificent, ridiculous sentences?

When Chekov used to visit the penal colony of Sakhalin, an island in a far-eastern area of Russia, he questioned all the prisoners and asked a photographer to take their picture. He wanted to make a book that included their portraits. The book was never written unfortunately, and some of the portraits have been lost. Of course the prisoners, uniformly dressed and in exile far from their home towns, bear no resemblance to the Muscovites who fill the pages of this book. But they are not entirely different. The slaves were tied to this island and to their prison sentence. Ahmet Sel, with a tenderness akin to Chekov’s, shows us today’s Muscovites, tied to their life and their city. Chekov explained that at the penal colony of Sakhalin, the main reason for break-outs was “love of the homeland.” He speaks about an old woman who was condemned and who acted as a servant when he visited, admiring his suitcases and books simply because these objects came from “home,” from Russia and its capital Moscow, which was and still is the centre around which life evolves. “To Moscow! To Moscow! the young countrymen chanted in one Chekov play.

The mirage continues. Each portrait taken by Ahmet Sel peels away and reveals the hidden Moscow and the life within. They show the other side of the Muscovite mirror and provide a wealth of sensitive information. Without indiscretion the photographs and the wandering eye of the photographer tells many stories while giving immense pleasure to those who look at them. When all the portraits are put together, they form an auto-portrait, not of Ahmet Sel, but of his reflection. How his life in Moscow and the years he spent there changed him and matured him like a vintage wine. This album is a slow panorama, a last emotional and determined look, a bit like one gives before closing the door one last time on a much-loved room.

Jean-Pierre Thibaudat

Click here for the “People of Moscow” series